|

|

|

|

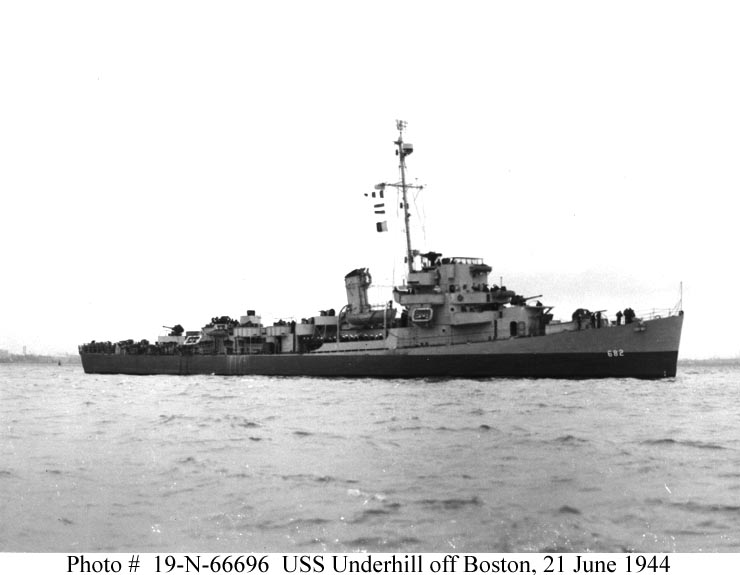

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE USS UNDERHILL DE-682 |

|

--By Stanley W. Dace, Chief Boatswain's Mate (Commissioned October 15, 1943 -- Lost in Action July 24, 1945) The USS Underhill was named for Ensign Samuel Jackson Underhill, US Navy flyer who was killed in action during the battle of the Coral Sea -- action which took place during the period of May 4 - 8, 1 Participating in offensive action against the enemy with aggressive skill and courageous determination in the face of tremendous anti-aircraft barrage, Ensign Underhill contributed materially to the sinking or damaging of eight enemy vessels in Tulagi Harbor on May 4th and to the sinking of an enemy aircraft carrier in the Coral Sea on May 7, 1942. Again, while on anti-torpedo patrol, he fiercely engaged in the combined attack of enemy bombing and torpedo planes and their heavy fighter support before being shot down by a Japanese zero. These were desperate times. For his part in action against the enemy, Ensign Underhill was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross, and became the name-sake for the USS Underhill DE 682. The Underhill and her crew would carry on the battle in the Caribbean and Mediterranean Seas and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans up until the last few days before the end of the war with Japan. The U S S Underhill is Launched The Underhill was commissioned one month later at the Fore River Shipyard with the supervisor of shipbuilding placing the ship in commission. The Ensign, the Jack, and the Commission Pennant were hoisted, and Lt. Commander S.R. Jackson, U.S.N.R., took command and set the watch. The USS Underhill was now a part of the United States Navy. On December 2, 1943, after trial runs and crew training, the Underhill moved to the Boston Navy Yard for provisioning and loading of ammunition. On December 2, 1943, she was underway to Bermuda, British West Indies, for further training and shakedown, returning to Boston Navy Yard on January 10, 1944 -- in dry dock for minor repairs. The ship got underway on January 22, 1944, for Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to run convoy duty between Cuba, Trinidad and other Caribbean ports. The Caribbean at that time was known as "Torpedo Alley", and it is suspected that the Underhill reduced the blackfish population substantially as the ship's crew dropped depth charges and asked questions later. Returning to Boston Navy Yard on May 30, 1944, the Underhill's torpedo tubes were removed and replaced with Bofors 40 millimeters and added two 20 millimeters on the fantail since the next convoy assignments would be in the Mediterranean ports of Bizerte, Tunisia; Oran,, Algeria. The German Junkers 88, converted to torpedo planes which were flying out of Southern France, had been taking a terrible toll on British-French convoys in the Mediterranean, so more air defense rather than surface defense was needed. The next convoy was to Plymouth, England, where the ship struck an underwater object in the English Channel, destroying the ship's Sonar soundhead. The object was believed to be a German submarine. Putting into British dry dock at Plymouth, it was found the British were unable to make needed repairs, so the Underhill returned to Boston (alone) for a new sound head. The Underhill's next convoy departed Norfolk, Virginia, on November 9, 1944, for Oran, Algiers -- Convoy Command CTF 60 -- returning to Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and Brooklyn Navy Yard on December 21st. She departed the Brooklyn Navy Yard for New London, Connecticut, on January 8, 1945, for training in anti-submarine warfare, damage control, etc. Assigned to 7th Fleet In the Pacific: *left Leyte Gulf for Hollandia, New Guinea, by way of Biak Island. *June 5, 1945, left Hollandia escorting troopship USS M.B. Stewart (AP-140) to Leyte Gulf. *June 10, 1945, departed Leyte for Hollandia. Enroute received "May Day" distress call from OA-10 #23 (Liberator Bomber). Diverted to crash site by orders of Commander of the Philippine Sea Frontier. June 12, search conducted in company with USS Thadeus Parker D.E. 369. *June 15, 1945, at 0600 USS Parker and airborne searchers abandoned search. At 0729 June 15th, Underhill lookouts spotted green dye marker and ration can floating on water. Officer of the deck changed course to investigate, and three survivors of the crash were found in rain squall off to starboard. Survivors brought aboard at 0759. *After rescue operations were completed, the captain ordered a course change to the original destination, Hollandia, N. G. to escort troop ship to Leyte Gulf. *Other ports included Manus, Admiralty Islands; Bora Bora, Society Islands; Palau, Caroline Islands. *Underhill's next convoy was to Okinawa. Departed Leyte Gulf July 9th with a large convoy of supply and troopships, arriving July 14, 1945. *Assigned radar picket duty until relieved to serve as Escort Commander of Task Force Unit 99-1-18, departing Buckner Bay, Okinawa, for Leyte Gulf on July 21, 1945. The 682's Final Voyage The Underhill had arrived at Buckner Bay to train and prepare for the coming invasion of the Japanese home islands. However, due to mechanical and other problems of the original escort assigned to the convoy, the Underhill was selected as a replacement. The convoy escorts other than the Underhill were the USS PC's 1251, 803, 804, 807, SC's 1306 and 1309, and the USS PCE 872. On the morning of the third day out, July 24, 1945, about 200 to 300 miles northeast of Cape Engano, Luzon, P.I., the Underhill's radar picked up a Japanese "Dinah" (bomber) circling the convoy about 10 miles out. Her crew immediately manned their battle stations and ordered other escorts to air defense stations, waiting to see what the pilot of the Japanese plane had in mind (which at that time was to stay out of our gun range and to establish a base course for later use by Japanese submarines lying in wait). After some 45 minutes, the Underhill crew secured from battle stations and ordered the other escorts to resume assigned patrol stations. During this time, an SC had developed mechanical problems and had to be taken in tow by PCE 872. The Japanese submarines, after establishing the convoy's base course, released a "dummy" mine in the path of the convoy. When sighted by Underhill lookouts, the ship's commander ordered a general course change to port. When the last ship had cleared, Underhill stood in to sink the mine. After repeated direct hits by the 20 millimeter guns plus 30-calibre rifle fire, it was determined to be a "dud", and a diversionary tactic by the Japanese submarines, the I-52 and I-53, and according to some eye witnesses, there was probably a third. This bears credibility due to the number of "suicide subs" (kaitens) released in the area. Japanese submarines of the I-52 class carried four kaitens each, and there were at least eight surrounding the Underhill. (The I-53 which sank the USS Indianapolis just five days later still had kaitens available.) Kaitens, once released, could not be recovered. After securing from the mine threat, a sonar contact made earlier began to look positive but was lost during course change. Underhill sonar regained sound contact and by TBS (talk between ships) guided the PC 804 into depth charge attack with unknown results. A few minutes later, a sub was sighted on the surface in the area where the 804 had dropped charges. The Underhill set a course to ram, but the sub was diving and the command was changed to drop depth charge. A 13-charge pattern was laid on top of the diving sub, and explosions brought up oil and debris. Underhill reversed course, reloaded K-guns and passed through debris. Sonar picked up another contact. The depth charges had brought to the surface a kaiten on the port side and one on the starboard side (these kaitens were about 35 feet long and carried the equivalent explosive charge of two torpedoes). The kaiten at starboard was too close in range for the main battery or the 20 mm or 40 mm to bear on target. The captain ordered all hands to "stand by for a ram". (Kaitens are capable of speeds to 45 knots). After ordering flank speed, and a course change to come to a collision course, the Underhill rammed the port side kaiten. After a few seconds, there were two explosions -- one directly under the bridge and magazine area, the second one forward of the bridge area and more to starboard -- which ripped the Underhill apart. The entire forward part of the ship was blown off forward of the stack. The stern section aft of the stack remained afloat. The bow, sticking straight up, was floating off to starboard. There was no panic among surviving crew members. Those who could helped 3rd class pharmacist mate Joe Manory with the wounded -- splints for broken bones, morphine for mortally wounded, cleaning fuel oil from flesh wounds. A fire in the crew's mess was extinguished by the damage control crew and remaining serviceable guns were manned by walking wounded in case Japanese subs would surface to try to finish the job. Lookouts were posted at the 1.1 AA gun and director. Searches were conducted for trapped crew members. Life rafts were jettisoned to use as lifeboats to pick up men blown over the side. This was accomplished by Machinist Mate 1/c Norman McCarty. A total of 112 crew member of the Underhill perished in the blast, while 122 survived. Ten of the fourteen officers were lost, including the captain, Lt. Commander Robert N. Newcomb. Every man was awarded the Purple Heart and Captain Newcomb also received the Silver Star. Rescue Operations by the PC's and LST The PC 804 had been the first to reach the combat site to assist with rescue operations -- hove-to about 300 yards off the starboard quarter of the Underhill. The 804 captain, using the "Bull Horn", asked the senior surviving officer, Lt. Elwood Rich, "I have a sub contact. Do you want me to come alongside to take your people off, or do you want me to go after the contact?" Before Lt. Rich could answer, one hundred plus crew members yelled as one voice, yelled "Go get that son-of-a-bitch". Such was the fighting spirit of the crew of the 682. With the survivors aboard the 803 and 804, a head count was taken. EM 1/c Rodger Crum and EM 2/c Paul Adams returned to the Underhill to assist CBM Stanley Dace in conducting a final search for any survivor unable to free himself. The rescue operation was completed. The surviving crew members had exhibited superior seamanship. It was a well-trained crew -- a credit to the Navy and to their country. Most of the survivors were in need of immediate medical attention, and a doctor and a pharmacist's made were taken aboard the PC 803 from the LST 647 to tend the wounded. The last small fighting ship lost to enemy action in World War II, the USS Underhill had been hit at 1515 (3:15 p.m.) on 24 July, 1945. The search crew left the Underhill at 1830 (6:30 p.m.) with CBM Stanley Dace the last man off the ship. Upon orders from the commander of the Philippine Sea Frontier, a firing line was formed by PC 803 and 804 and PCE 872 to sink what remained afloat of the Underhill. The stern section and bow were sunk by gunfire at 1917 (7:17 p.m.). The remainder of that fateful day of July 24, the two PC's were enroute to catch up with the convoy -- which had escaped damage by the enemy -- and upon rejoining the convoy, transfer of the Underhill survivors to the LST 768 began at 0300 (3 a.m.) on 25 July. Upon completion of the transfer, the convoy, Task Force Unit 99-1-18, then proceeded to its destination of Leyte Gulf. While the USS Underhill 682 and 112 of her men had been lost, she had accomplished her mission -- that of delivering her convoy safely to its destination. Captain Neale O. Westfall, U.S.C.G. Ret., then communications officer of the LST 768, in speaking of his memories and recollections of July 24 and 25, 1945, at a recent Underhill reunion, said that in his opinion, there was no doubt that the Underhill's aggressive action had saved the convoy. In her short lifetime in the service of the US Navy, in all her missions and assignments of convoy duty on both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the Underhill did not lose a single ship to enemy action -- something of which her crew members, past and present, should be justifiably proud, and we think Ensign Samuel Jackson Underhill would be proud of his namesake. |

| [Home] [New Additions] [About Underhill] [Namesake] [Last USAF Survivor] [1st Ann. Dinner] [Thanksgiving] [To The Rescue] [Underhill Pictures] [Untitled189] [July 24th 1945] [Crew Information] [Kaiten Information] [Stories] [Reunion Information] [In Memory] [News & Events] [Photos Page] [Links] [Guest Book] [Founding] [Dedication] [Site Award] [About This Site] | |||

942, in the early months of World War II.

942, in the early months of World War II.